For many of us, some of our fondest childhood memories are associated with the stories and books we learned from our parents, heard from our teachers, and discovered for ourselves—this article dives into the history of children’s literature so that we understand the origins of the stories we treasure throughout our lives.

For many of us, some of our fondest childhood memories are associated with the stories and books we learned from our parents, heard from our teachers, and discovered for ourselves—this article dives into the history of children’s literature so that we understand the origins of the stories we treasure throughout our lives.

The memories of stories dear to our hearts persist through today, weaving themselves into our lives as adults. For me, simply seeing a chrysanthemum makes me nostalgic for the picture book of the same name, which I couldn’t stop rereading as a Kindergartener, and an old coworker continues to read A Wrinkle in Time every year of her life, well into her thirties.

The importance of children’s literature cannot be understated; the habits and associations we hold as a result of these stories underscore the indelible charms that children’s books cast over minds. We just can’t seem to break the spell of imagination and wonder. But why should we even want to? What accounts for this spell, and are today’s children just as transfixed as my cohorts and I were at their age? What constitutes a successful book for children, and do the same standards remain constant over time? I sought these answers from libraries and from librarians, but along the way I realized I had a lot to learn about the actual history of children’s literature as a unique, qualifiable genre.

The Conception of “Childhood”

It may appear self-evident that children’s literature had to be invented, that children did not always read beautifully illustrated books with simple plot structures and flowing prose or poetry. However, before children’s literature could be invented, the actual institution of childhood had to be invented, for just as propriety and aesthetics and almost everything else remain in constant flux over decades and centuries and millennia, so do social statuses and their respective roles.

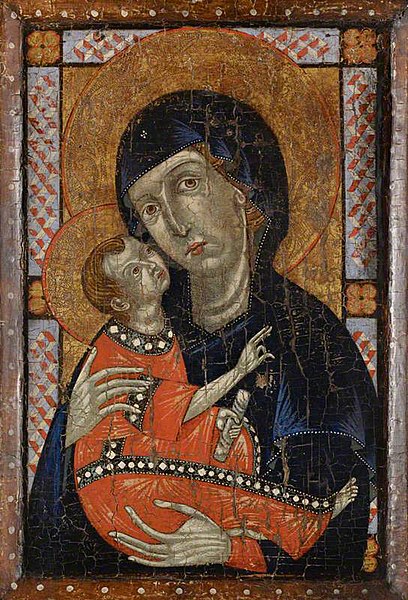

Case in point: before the Renaissance, society viewed children as miniature, functioning adults—if you observe the painting to the right, you can see an example of how the children that medieval and early-Renaissance artists painted look like tiny adults, with the clothing, posture, and even wrinkles of adults, lacking many features seen in children. Their role in day-to-day affairs were no less important than those of mom and dad. As such, separate forms of entertainment for children did not exist. Children merely consumed the same forms of entertainment as their adult “peers,” only in redacted form. Just as the lines between childhood and maturity were blurred, so were the lines between children’s and adults’ literature.

It wasn’t until the advent of the Renaissance—and, notably, of the movable printing press—that it became feasible from economic and mechanical points of view to increase the production of educational materials. With the expansion of trade routes and conduits for knowledge-exchange (facilitated in large part by the Crusades), a new middle class emerged which could temper leisure and cultivate education. As a result, educational materials specifically targeting children could be produced more economically in greater volumes, and parents and educators could devote more time to rearing children, cater to their unique needs, and develop childhood as an institution distinct from adulthood (Bingham and Scholt).

The First Children’s Stories

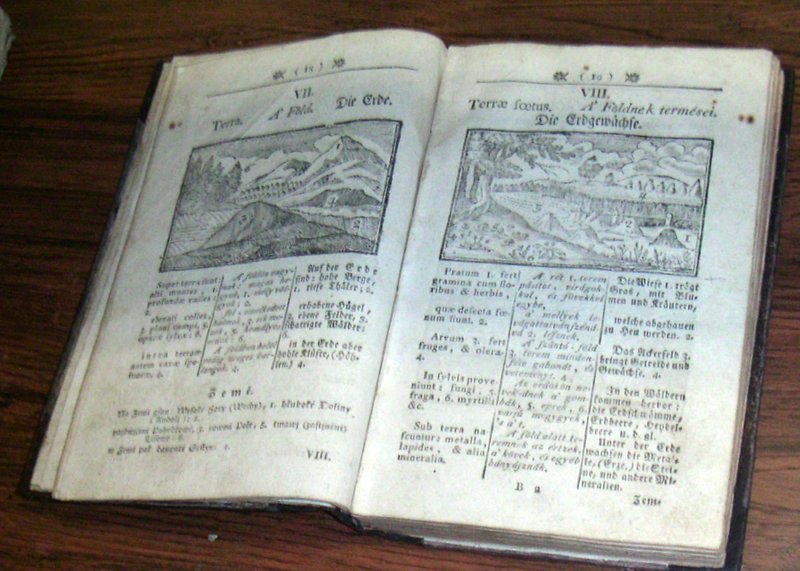

The majority of the children’s literature produced at this time, i.e. during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was didactic in nature and included gruesome tidbits from the status quo such as disease, war, and famine. These stories often took the form of dialogues between teachers and pupils and rhymed couplets and stressed morality and manners. However, in a departure from the prevailing norms, in 1658 Johann Amos Comenius published his Orbis Pictus (The World in Pictures), which took the form of woodcuts illustrating several everyday objects. Even if the book’s aims were closer to pedagogy than to recreation, Comenius’s work is nonetheless considered the first picture book for children (Hunt).

Still, children’s literature was quite far from being all fun and games, as it were. At the end of the seventeenth century, with their doctrine of individual salvation, the Puritans held that children had to be preserved from eternal damnation. To them, literature held the role of preparing children for salvation and safeguarding them from hell; not surprisingly, then, the majority of Puritan literature portrayed children facing grim life-and-death scenarios wherein they had to rely on a supreme moral compass. It was thus children’s spiritual lives, rather than their physical surroundings or social interactions, which Puritan parents emphasized and Puritan literature reflected the most (Bingham and Scholt).

It was not until the advent of philosophers John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the late seventeenth–mid eighteenth centuries that children’s literature took on a more playful, jovial character. Locke was a firm proponent of the idea of childrens’ clean slate, or tabula rasa, on which adults could impose their mores, morals, and ethics. Following Locke’s Enlightenment philosophy, literature could be used to influence, educate, and guide the child, but only if said literature was pleasurable and entertaining. Locke exhorted parents to promote reading as a leisurely, fun activity for their children and urged authors to create pleasant, enjoyable children’s books, all in an effort to aid children’s retention and application of important life lessons.

Rousseau, on the other hand, emphasized children’s autonomy in their development. Unlike Locke and his notion of the tabula rasa, Rousseau stressed that children grow at their own pace and perceive the world in their own terms and frames of reference. To him, childhood was the language of the “noble savage,” i.e. the utmost form of simplicity and innocence. According to his romantic worldview, children were to be treated as competent, precocious readers who had unique, independent capacities for appreciating aesthetics. Successful children’s literature, then, would seek to cater to the child’s world-view in an effort to identify and align, rather than mold and change.

The Novel and the Picture Book; Growing Innocence and Imagination

Enlightenment and romantic philosophy both left indelible impressions in the further development of children’s literature as a unique, burgeoning genre. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, around the period of time wherein Locke was working, experts point to how “changes in philosophical thought as well as the rise and growing refinement of the middle class allowed children to become more sheltered and more innocent.” Childhood’s retreat to a separate sphere of life helped usher in what several consider to be the beginning of two new forms of children literature in the Anglophone world: the novel and, most importantly, the picture book.

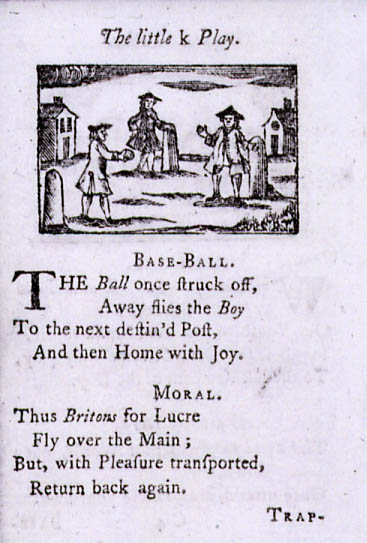

John Newbery, influenced by John Locke’s ideas on pleasure reading and pictures as pedagogical tools, published Newbery’s Pretty Pocket Book in 1744. What makes this book so outstanding is that, by attempting to teach children the alphabet “by Way of Diversion,” it was the first book openly and unabashedly aiming to amuse its readership. The book’s multi-media format—which includes pictures, rhymes, games, and fables—was certainly novel for its time as well, and its subsequent success proved to Newbery and future publishers that children’s literature could be tempered and marketed as a lucrative means unto itself.

At this point, there existed several different genres of children’s literature: games, fables, alphabet books, nursery rhymes, poetry, and fairy tales. Throughout the nineteenth century, following the trend established by Newbery’s work, children’s literature became increasingly less didactic in nature and more geared towards children’s imagination and empathy with the reader.

Advances in printing technology also made it possible to mass-produce beautifully detailed pictures at hitherto unheard of rates, thereby paving the way for the profession of the illustrator. With the influx of immigration to the United States, several talented authors and illustrators from Europe contributed to the growth of children’s literature on the other side of the Atlantic as they settled in new lands, thereby increasing the market and demand for children’s books.

Children’s Books as Vessels of Ideology

Joosen and Vloeberghs are quick to note the link between ideology and children’s literature, and this flourishing epoch in the history of children’s literature certainly demonstrates how literature enforces social norms and conveys societal world views. For example, in their portrayals of brave, heroic men and boys coupled with quiet, virtuous women and girls, children’s literature helped uphold gender norms which by today’s standards would seem antiquated and patriarchal.

Moreover, it bears mentioning how British children’s literature predominantly featured adventure in distant, dangerous lands, whereas American children’s literature often told “rags to riches” stories wherein the hero is able to surmount economic obstacles and ultimately find success and renown. By incorporating such subject matter into their respective canons, British and American literature of this time reinforce socio-political reality and ideals by including motifs taken from ideology and immigration/the so-called “American Dream” respectively.

The twentieth century saw the development of fantasy as a popular genre for children. Childhood became an increasingly protected sphere of life, and as such, elements meant to provoke terror became increasingly dilute in literature for younger audiences. During the age of the Puritans, fear played a critical role in preparing children for the afterlife; now, fear lost its educating force as it became absorbed into the genre of fantasy. The first fantasy books for children (such as The Wizard of Oz, The Hobbit, and The Little Prince) were originally meant for adults. It was not until the 1950s and 1960s that children’s fantasy began to thrive; even then, fear became transformed from a didactic pathway to an aesthetic experience.

Social commentators are keen to posit possible links between the boom of fantasy for children and adults and responses to the Cold War and to the growing drug culture in the United States. Similarly, the civil rights movement in the 1960s forced children’s literature authors to recast depictions of race, gender, and social narratives in their works. Characters became less white-washed and more nuanced, and those from parallel cultures began to step into the forefront as authors began to question and re-examine what exactly constituted the American experience. Subject matter also became increasingly grittier, as authors strove to incorporate socio-political reality into their works and identify with a new generation of diverse readers. In this era, the classic children’s literature we know today was born. In “Charlotte Huck’s Children’s Literature,” twentieth century children’s literature is summarized as follows:

“Just as adult literature mirrored the disillusionment of depression, wars, and materialism by becoming more sordid, sensationalist, and psychological, children’s literature became more frank and honest, portraying situations like war, drugs, divorce, abortion, sex, and homosexuality. No longer were children protected by stories of happy families. Rather, it was felt that children would develop coping behaviors as they read about others who had survived problems similar to theirs.”

Empathy now stands on even ground with pedagogy in children’s literature, and audiences are now invited to participate in literary spaces where their backgrounds and experiences are not only recognized and reflected, but also preserved and validated.

Literature and ELA Learning with Piqosity

The history of children’s literature shows that the way adults and society view children has never been uniform, shifting along with the zeitgeist. From viewing them as mini-adults to the creation of “children” as a class of personhood, adults have always been tasked with understanding what to do with children—do we utilize their tabula rasa state of being and sculpt them into being the “best” adult, or allow them freedom to discover the world and make what they wish of it? Or, is there a perfect balance between all approaches?

Throughout the many changes to the way children are regarded, a constant is the responsibility to educate them and equip them with the necessary knowledge to mature in our world. For 5th graders and older, Piqosity is here to help with academic needs. In addition to our full test prep courses for the ACT, SAT, and all ISEE levels, we offer full English and Math courses for grades 5-11 online through our app, which can be purchased separately or received for free when bundled with our ISEE test prep courses.

Each of our English courses includes more than 100 reading passages, including short stories, nonfiction and argumentative essays, and at least one full novel! For example, our ELA 6 course includes passages from Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer as well as Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Each passage is paired with reading comprehension questions in a range of difficulties suitable for the grade level, written by our team of educators to quiz students on their ELA skills.

Full-Length ELA Courses:

- 5th Grade English Course

- 6th Grade English Course

- 7th Grade English Course

- 8th Grade English Course

- 9th Grade English Course (New!)

- 11th Grade English Course

More Educational Resources by Piqosity:

- 5 Books for 5th Graders to Read Over Break

- The Best OER Materials for K-12 Teachers

- 10 Books to Improve Vocabulary Acquisition

- Tips for Reluctant Readers: How to Foster a Love for the Written Word

- Modern Children’s Literature: The Twentieth Century and Beyond

REFERENCES

Bingham, Jane and Grayce Scholt. 1980. Fifteen Centuries of Children’s Literature: An Annotated Chronology of British and American Works in Historical Context. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

“The Changing World of Children’s Books and the Development of Multicultural Literature” from “Charlotte Huck’s Children’s Literature.” http://highered.mcgraw-hill.com/sites/dl/free/0073378569/669929/kei78569_ch03.pdf. McGraw Hill. Web. January 15, 2013.

Hunt, Peter, ed. 1995. Children’s Literature: An Illustrated History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

“To Instruct and Delight: A History of Children’s Literature.” http://www.randomhistory.com/1-50/024children.html. Random History. January 29, 2008. Web. January 15, 2013.

Joosen, Vanessa and Katrien Vloeberghs, eds. “Changing Concept of Childhood and Children’s Literature.” http://www.c-s-p.org/flyers/9781904303794-sample.pdf. Cambridge Scholars Press. 2006. Web. January 15, 2013.

This article was originally published on ThesisMag.com and written by Evan Alterman.

Leave A Comment